Shushtar New Town

LOCATION

Iran Khuzestan

Year

1974-1980

(partial completion)

Population 30 000-40 000

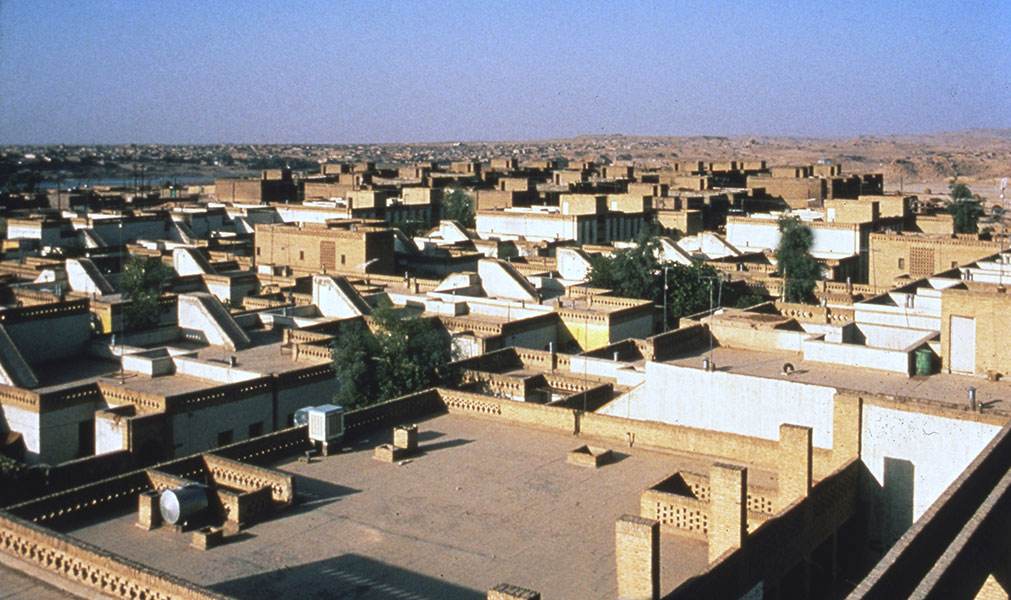

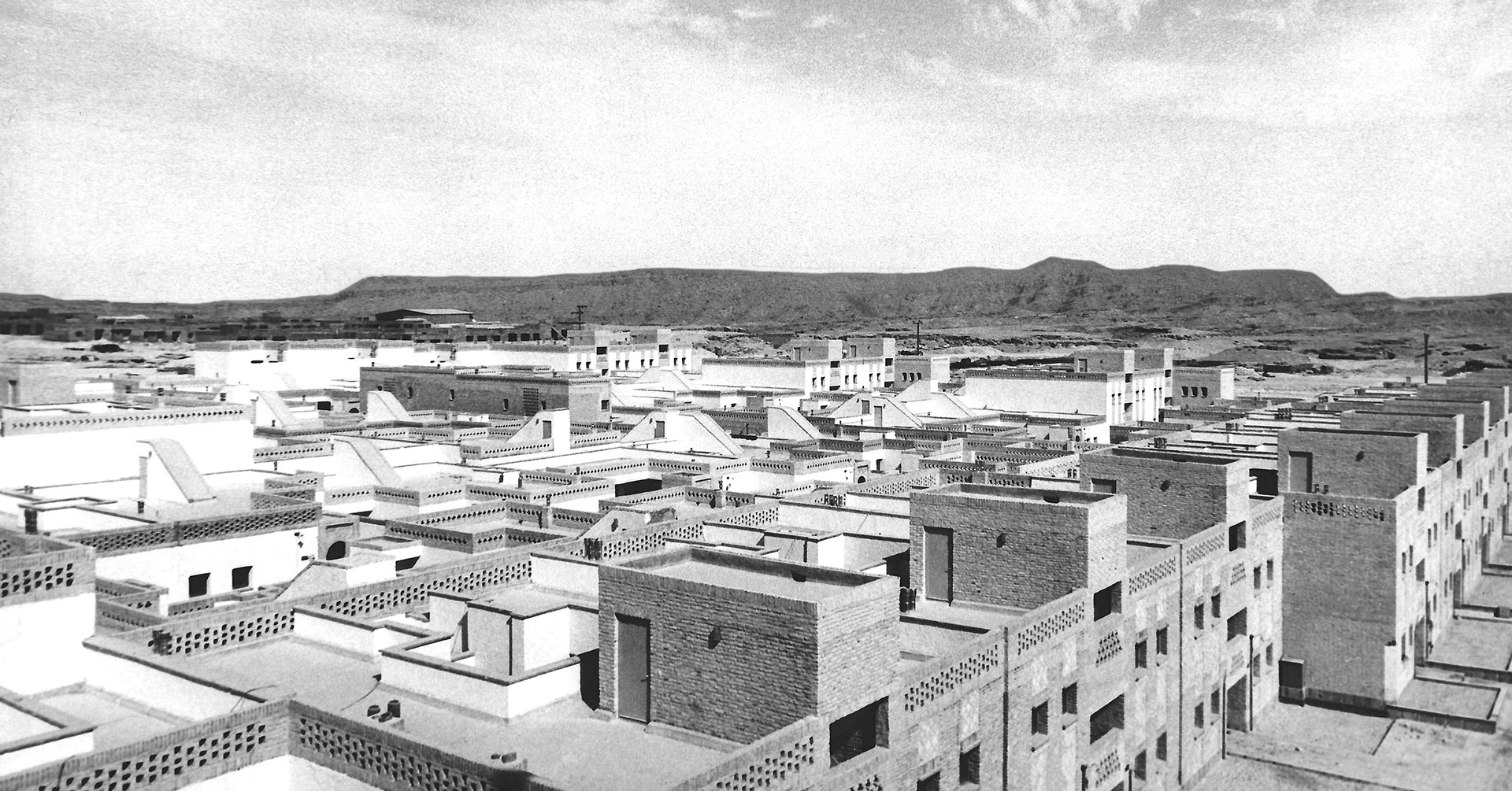

This is a town for workers and employees of the Karoun agro-industry located across the river from the historic town of Shushtar. During the seventies in Iran many new towns were being built. Unfortunately, few attempts were made to incorporate vernacular architecture on such a scale as Shushtar. In the beginning, our client gave us quite a bit of trouble and interfered in the design of the project. This is very typical of developing countries where the technocrats feel that since they have a more powerful position than architects, they are free to implement their own taste and ideas into the projects they undertake. Fortunately, after a preliminary struggle with many different agencies which were involved in the investment, we succeeded, under a very tight schedule, in putting together a new town which is sympathetic to the cultural values of Iranian society and yet maintains a traditional continuity with the past.

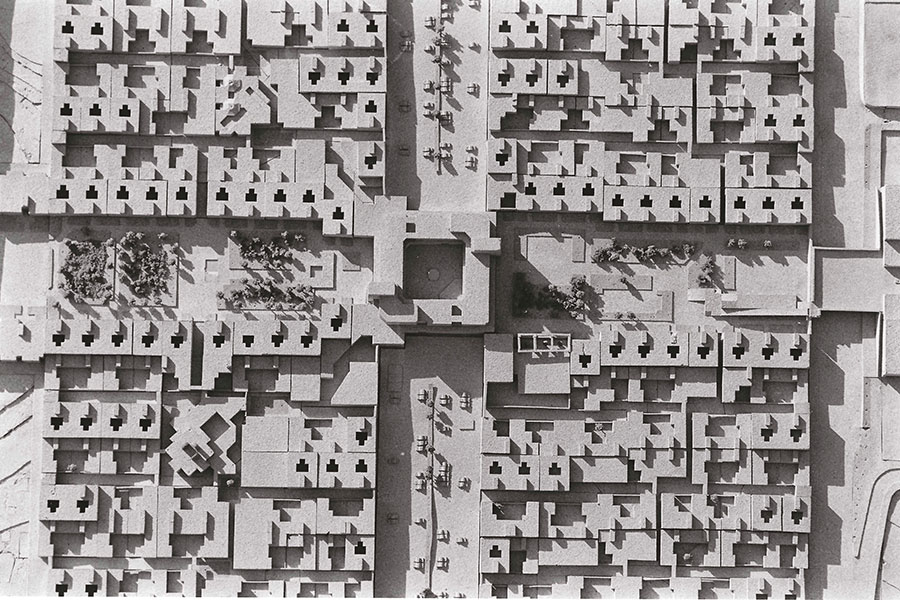

The major design feature is a multi-faceted central east-west pedestrian boulevard. This consists of many gardens, paved squares, covered and shaded resting places, arcades, bazaars, pedestrian bridges complemented by dramatic changes of level and decorated with lush plantations, fountains, running water and occasional use of Persian mosaic tile work. The neighborhoods are designed to encourage movement in the direction of this pedestrian boulevard. Major public activities, such as schools, bazaars and a variety of community affairs occur along this spine, enhancing its prominence. The contrast of the narrow-paved streets of the neighborhoods, which are almost treeless, makes the boulevard a very precious place with strong image-ability. This also worked out as a practical solution because of maintenance and landscaping costs which we considered difficult and luxurious for this scheme. We located many private gardens in such a manner that their vegetation could provide shade and a green touch to the narrow streets.

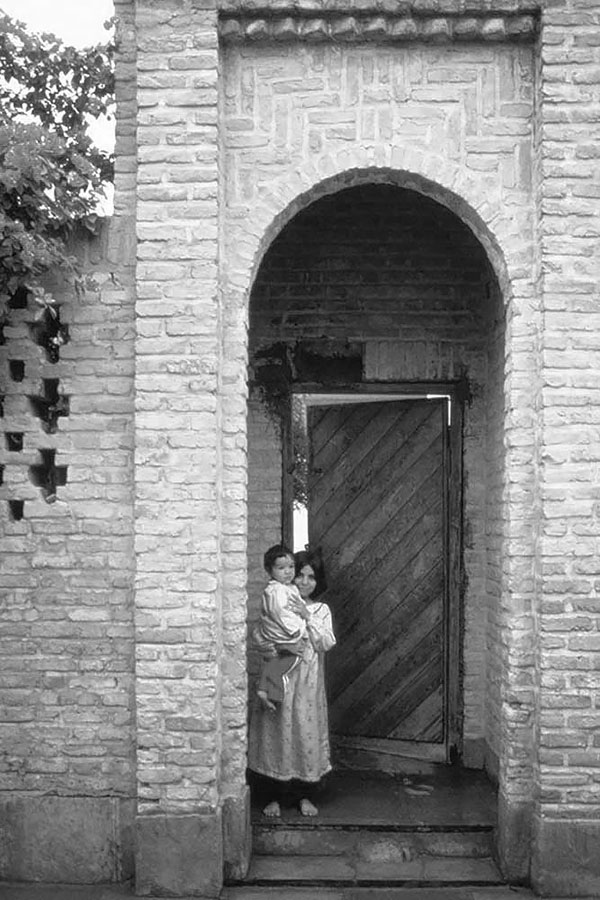

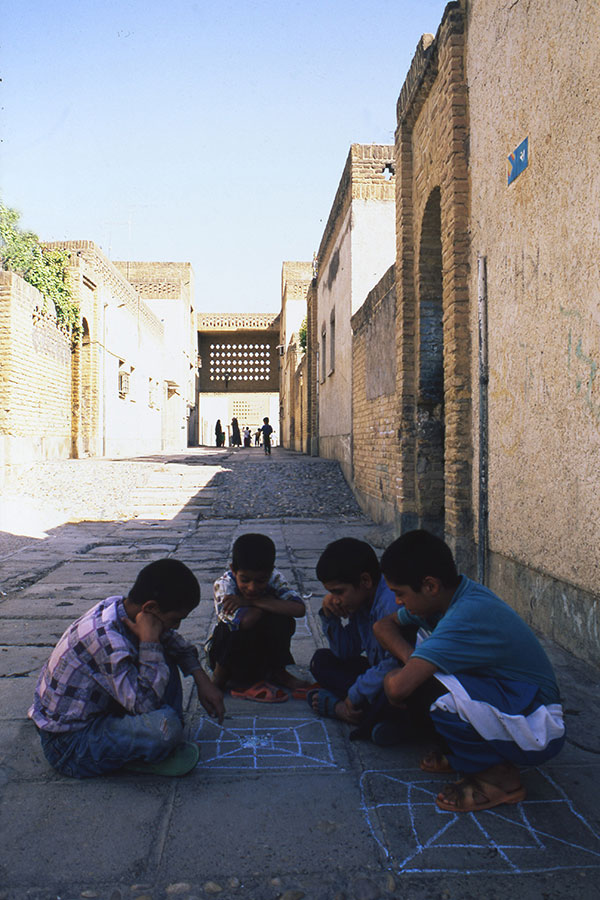

The streets were designed not primarily for a corridor-like function, but to generate and maintain a life of their own. Observation of old cities showed streets as a kind of playground or meeting-place; so, we created a lot of dead-end streets which preserved privacy and identity.

We managed to segregate the automobile from internal community life and also approached the whole project as a high-density horizontal apartment house, with all parking areas concentrated collectively at strategic points.

One of the concepts incorporated into our scheme was that the western notion of thinking of a house as a conglomeration of living-room, dining-room and bedrooms, was abandoned. We concentrated on the room as a flexible interior unit, since, historically in Iran hard furniture was never developed and instead large multi-purpose, multi-functional spaces were provided. Having the influence of a very strong nomadic culture, Iranian houses are not only adaptable to different daily functions, but also, in a typical courtyard house, according to the season, the inhabitants move around the courtyard to avoid or enjoy the sun.

We made two and three-room housing units planned in a manner in which they could simply expand to the next unit and become a four, five or six-room house. The idea was to avoid the eternal stigma of low-income housing and minimum room sizes. As the standard of living improves, the houses would be expanded, and families could have larger dwelling units. The argument was that the Iranian way of life, especially the non-western style prevalent among low-income groups and the rural population, needed less rooms but larger spaces to accommodate different daily and nightly functions. The majority of rooms were 5×5 m and the smallest rooms were not less than 4×4 m or 3×4 m. We also concentrated on houses rather than apartments. Close to 90% of dwellings are one or two-story houses and all units are provided with a garden which is designed as an outside room without a roof. The new town is programmed to integrate different income groups. In order to further reduce the institutional (company town) character of the new community, it was planned that a percentage of houses built by the company should be offered on the open market to attract and assimilate the natural growth of adjacent old Shushtar into the new town.

Beyond accommodating the functional needs of a scheme, I am very much concerned about the physical stage we set for patterns of social interaction and collective behavior. Obviously, this objective is an involvement beyond just making buildings and is often incorporated into the program and design processes. Anticipating community and social behavior, the question is: what happens when the architect leaves and the people move in?

First Phase Neighborhood

1974-1978

Due to the tight schedule and pressure from the client, the first neighborhood was designed simultaneously with the master plan. We designed the first neighborhood as a total architectural unit, more like one building rather than loosely organized units within an urban structure.

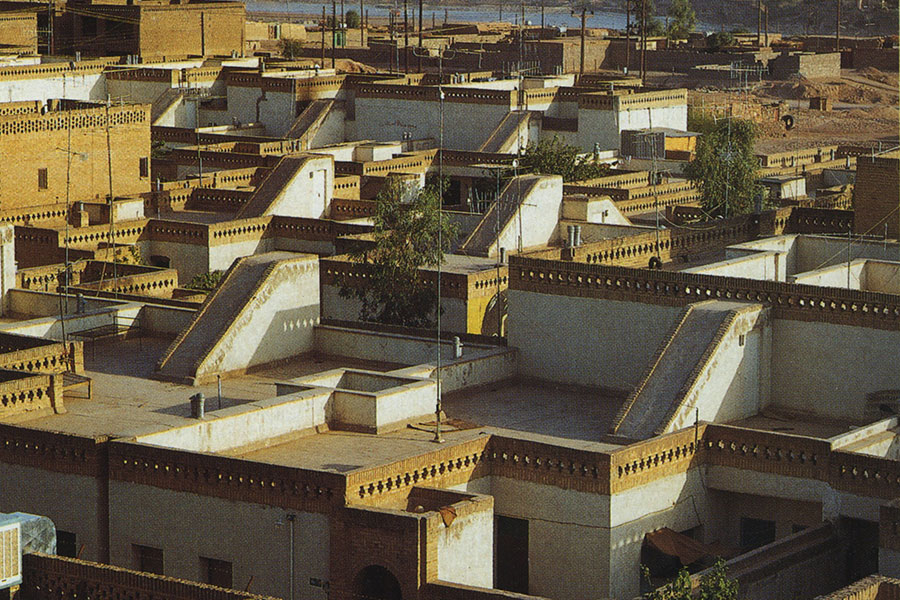

The houses, only three basic types, consisted of two to four rooms plus kitchen and bathroom. Room sizes were generous, 5×5 m, which allowed them to be converted to a variety of activities – sitting, dining or sleeping. Persians from rural areas and small towns use removable soft furniture like pillows and mattresses which are designed to be stored away daily as the function of the space is changed. In addition, we designed the units to be expandable to the adjacent unit by removal of the courtyard wall, so one small house could easily expand sie lager me. The insibily step trading the house

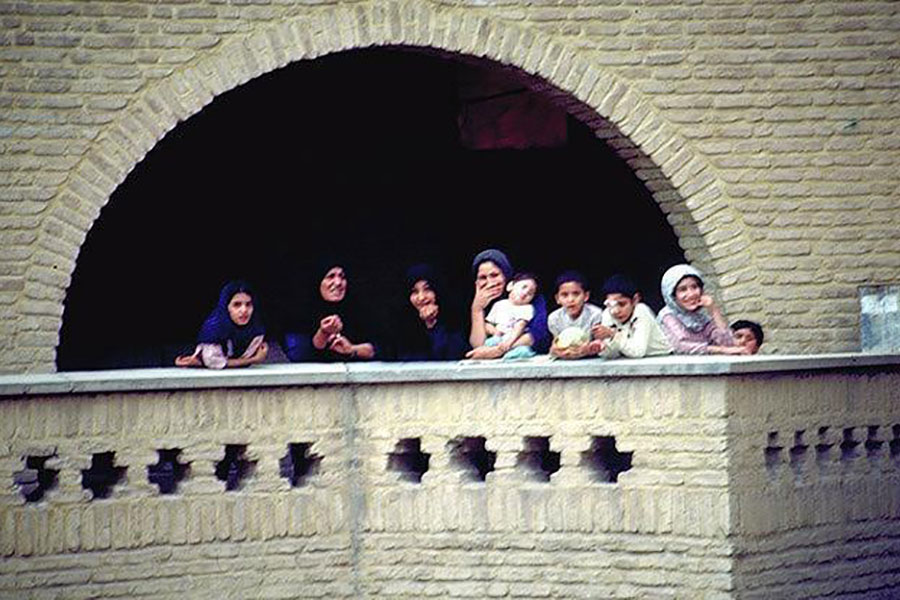

the neighborhood easy and provide inborn dynamics for socio-economic mobility. All units have a courtyard which, in Shushtar weather, could be used as a big open-to-sky room. Also, roof terraces were moderately screened to provide privacy, as it is customary to sleep on the roofs, where one can enjoy the cool breeze of the night and contemplate a sky full of brilliant stars.

The streets, which are pedestrian and serve only a limited number of houses, are further extensions of houses where children play and parents chat. The basic attempt was to create a socio-physical entity conducive to collective interaction, togetherness and strong community ties.

Part of the green main linear pedestrian boulevard was designed with a neighborhood plaza and shopping center at the crossroad of vehicular and pedestrian access. Large parking lots were anticipated for the future but are used at present as sports and play areas (fig. on opposite page).

Neighborhood Plaza

1975

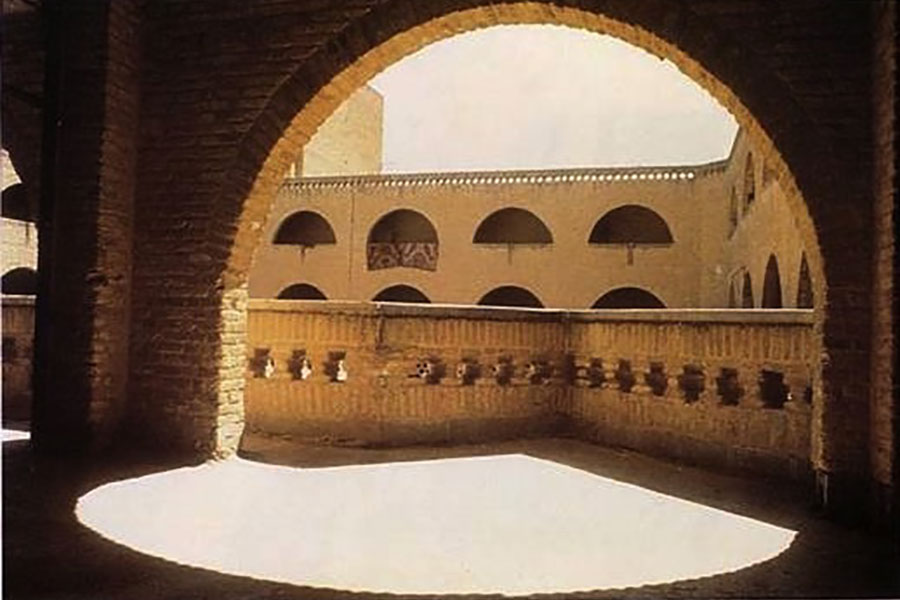

(under construction)

The arcaded shops and a hostel on the upper floors enclose this plaza which has access to the pedestrian boulevard, the parking lot and the narrow streets of the neighborhood. The tall interior elevation provides constant shade and as air circulates through the north-south axis, this area becomes an agreeable refuge from the blazing sun. The plaza is all paved and a space is allocated for an outdoor teahouse and small fountain.

From the terrace of this structure, one has a view of the entire new town and across the river, of the old historic Shushtar.

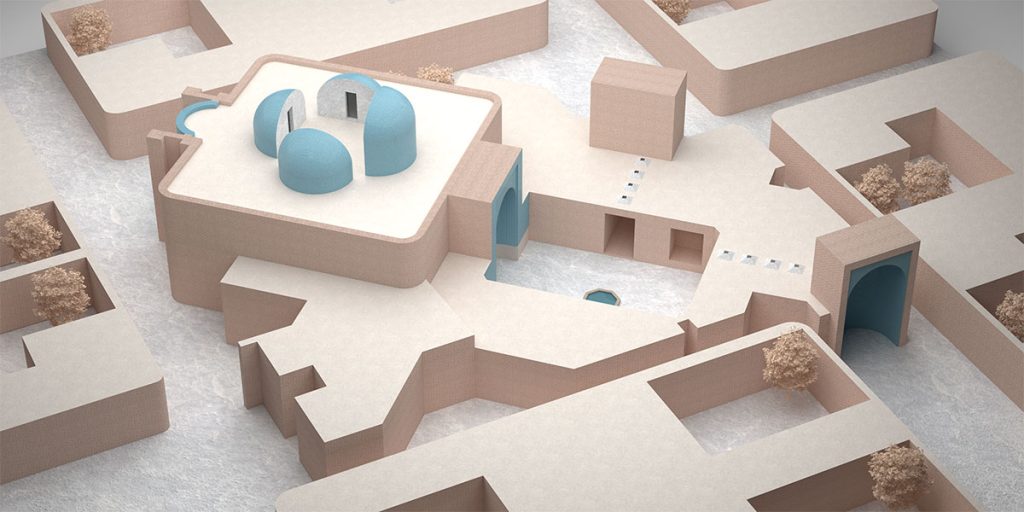

Neighborhood Mosque

1974

(under construction)

In order to break the monotony of the horizontal grid and give individual character to each block, we used the following means: north-south alleyways, open play areas, a bath house, central neigborhood plaza and, finally, a mosque. Each of these structures has an impact on the block and its immediate environment. The mosque courtyard, decorated with colorful mosaics and ceramic tiles, links into the pedestrian network, enhancing the quality of public spaces. At the time the design was being undertaken, Hossein Zenderoudi, an Iranian artist who works with calligraphy, was commissioned to make the mosaic and ceramic design.

Maidan-e-Shahr

1974

(under construction)

The Maidan-e-Shahr is the main and largest city square lying on the riverbank across from the historic city of Shushtar. The maidan, terminal point of the pedestrian boulevard, is ultimately meant to connect with the main street of the old city by a pedestrian bridge. This plaza, with dimensions of 100×100 m or 330×330 ft., encompasses major urban activities and is intended as the principal urban space unifying old and new town.

The program consists of government offices, a hotel, apartments, offices, arcaded shops and cinemas providing a variety of social events and activities.

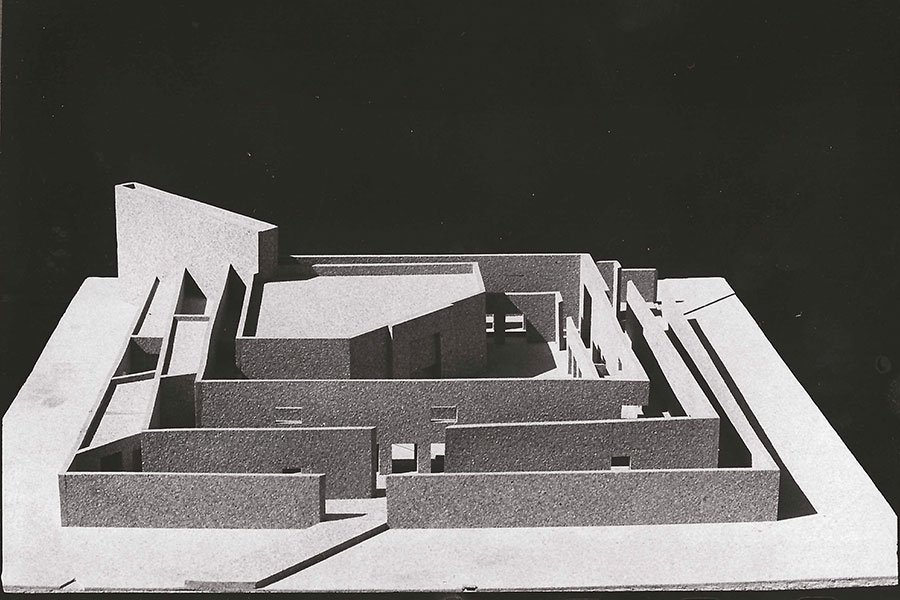

Friday Mosque

1977

The most ambitious mosque in the town is located at a high point of the site, in a commanding position overlooking the river and old town. This structure, like many other major buildings, was designed as part of the main boulevard which passes through the mosque’s corridor.

The mosque is located at the midpoint of the long pedestrian boulevard marking the open space on the edge of a ravine which physically divides the city into two primary levels.

We devised three different layers of walls to further remove the core of the mosque from daily intrusions. The mosque is, therefore, in a sense easily available for one’s daily excursion, but actual entrance means the extra effort of unveiling it further and further. The repetition of interior walls also allows us to orient the final courtyard space toward ‘gebbleh’ the Holy Shrine of Mecca, which is an unavoidable prerequisite of mosque architecture. A deep, tall interior space was devised to further emphasize the ‘gebbleh’ orientation. We introduced small cavities to allow natural light rays to penetrate into this dark, mysterious space.