Jondi Shapour University

LOCATION

Ahwaz Iran

Year

1968

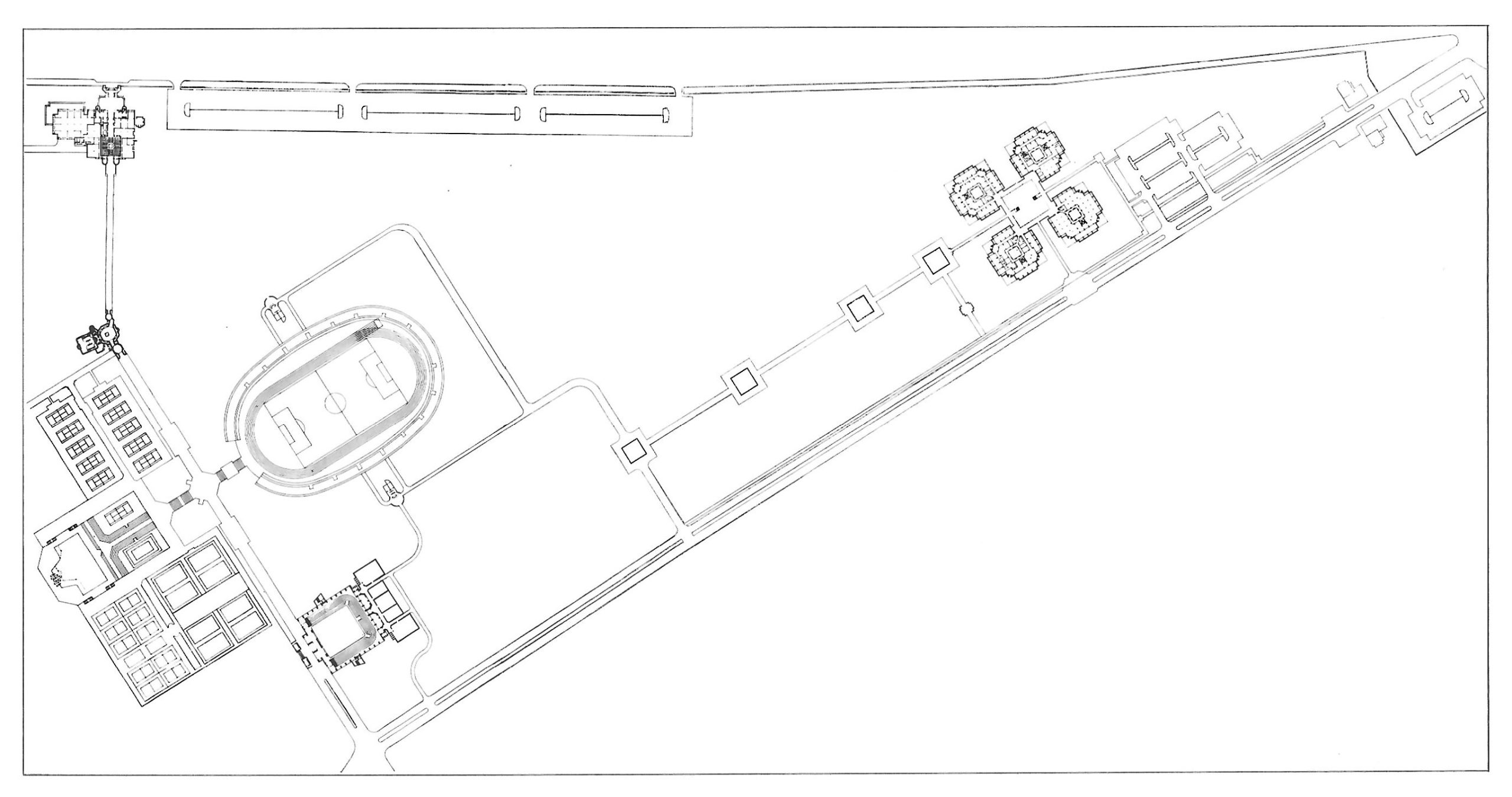

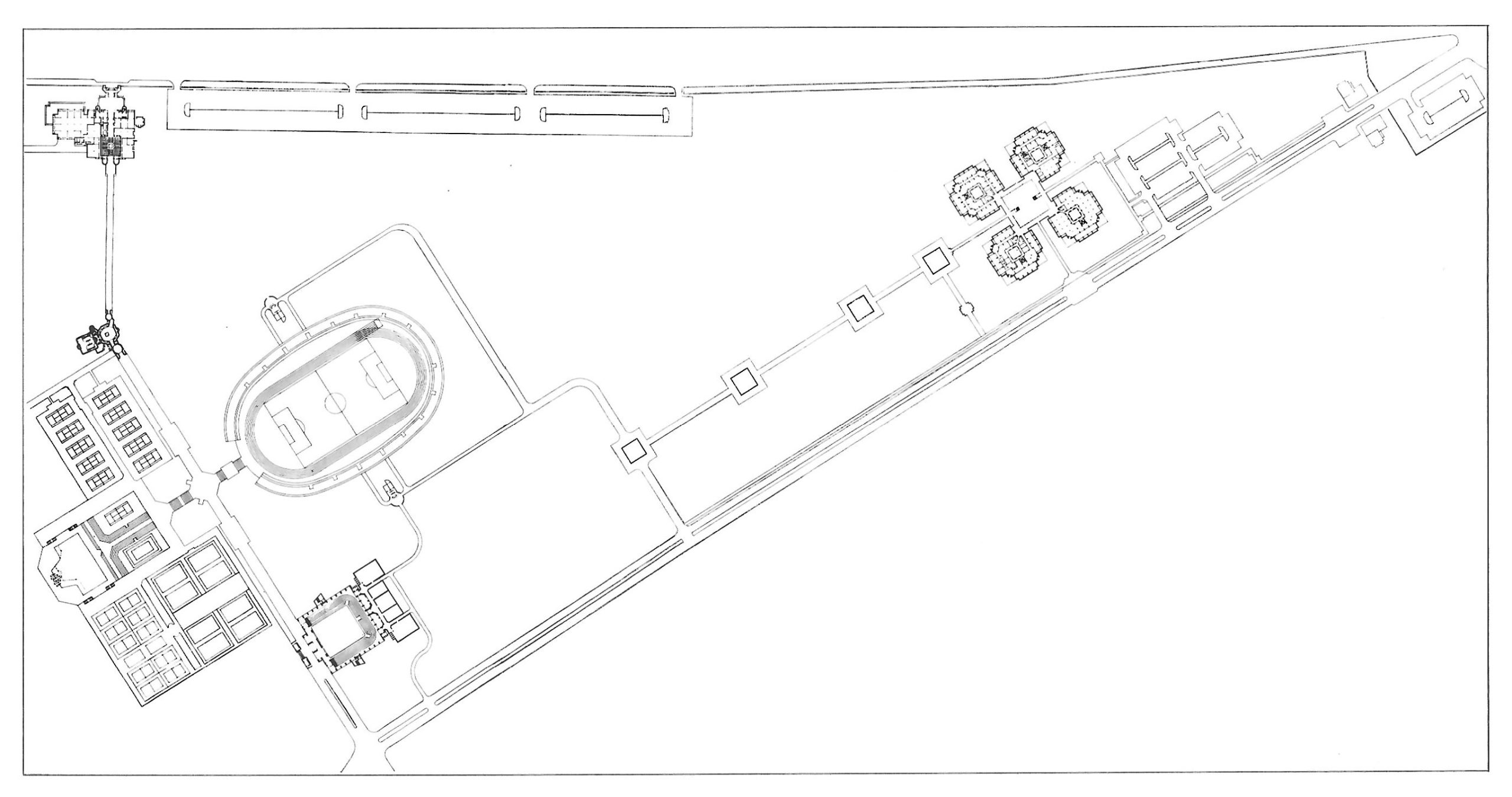

The new campus of the university is located near the Karoun River, on barren, flat land next to a lush botanical garden. The campus had been laid out by a variety of planners and the university chancellor, often with conflicting ideas and approaches. The university thus did not have a comprehensive plan when the west side of the campus was assigned to us. It was zoned for sports and non-academic support facilities.

Because of the lack of a general program, an attempt was made to create a pedestrian walk which could accommodate various activities and types of buildings.

The result is architectural space (sometimes open to the sky) of various scales, moods and interests along this walkway. The site was originally flat and barren, with the exception of an irrigation canal. This seemed to be a constraint at first, but later on was successfully integrated into the plan. Building no. I is the Student Union and Cafeteria, facing the street. The building is meant to be the pedestrian gateway to the campus, and so was designed with two towers. It marks the beginning of the walkway, and takes one through a narrow passage to a courtyard with a fountain. The latter is surrounded by a teahouse and other shops. Continuing from the court-yard, one finds a wide space with trees, lawns, and flowerbeds. Beyond this is an inviting doorway to the university’s small mosque (no. 2) which awaits the pedestrian traffic.

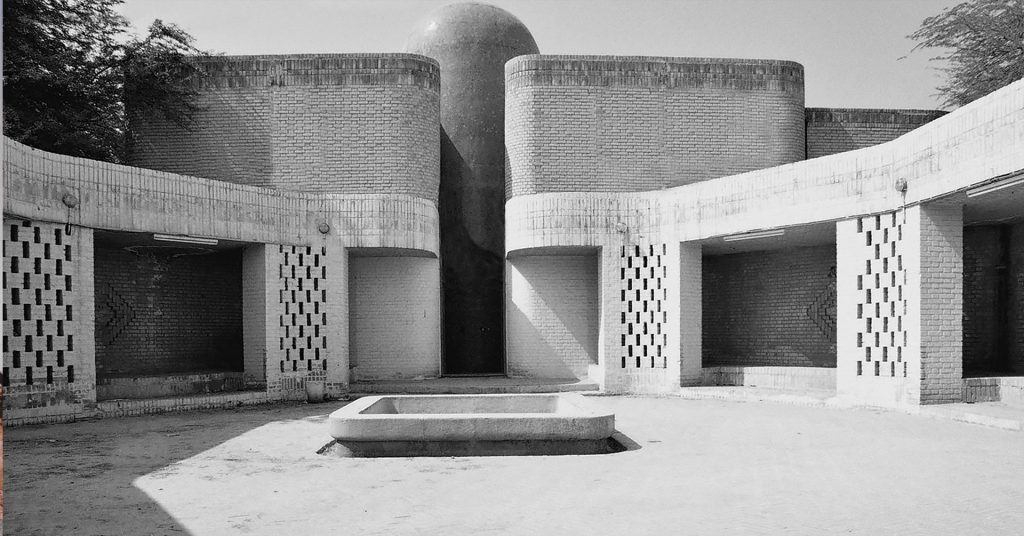

The courtyard of the mosque gradually unfolds as one enters the mosque through an unlighted passage. In the middle of the courtyard are a small pool and drinking water. The arcade provides shaded seating space. In its relation to the scale of the courtyard, the blue tile tower which marks the entrance to the mosque emanates strength and color in an all wheat-color brick environ-ment. The passage through the mosque courtyard involves a directional change in the pathway which is not immediately obvious to the user as he becomes involved in the intricacy of the mosque environment.

In this structure, sharp corners are avoided in order to create a soft, friendly, happy mosque, and to distinguish it from other buildings. As one proceeds through this courtyard, one encounters a small open-to-sky rotunda which effectively frames the sky and is also an opening to either continuation along the same road or a deviation to the south (academic zone). After leaving the mosque, a completely unexpected environment is unfolded. Continuing along the east-west walk and leaving the mosque, one arrives at an elevated level (the agricultural water canal) which is designed as a pedestrian promenade (no. 3) with trees, flowerbeds, lawns, benches and constant running water. The elevated level of this promenade gives one command of the tennis, volleyball and basketball courts and, further away, the soccer field. These are situated along the walkway with the intention of creating visual and interactional stimulation for the passer-by as players run about in colorful costumes. The sports activity beyond the mosque is a surprise to the first-time visitor, as each building sets the stage for a new environment and experience with different content, meaning and mood.

Continuing, one reaches an intersection which is connected to the main north and south sports grounds.

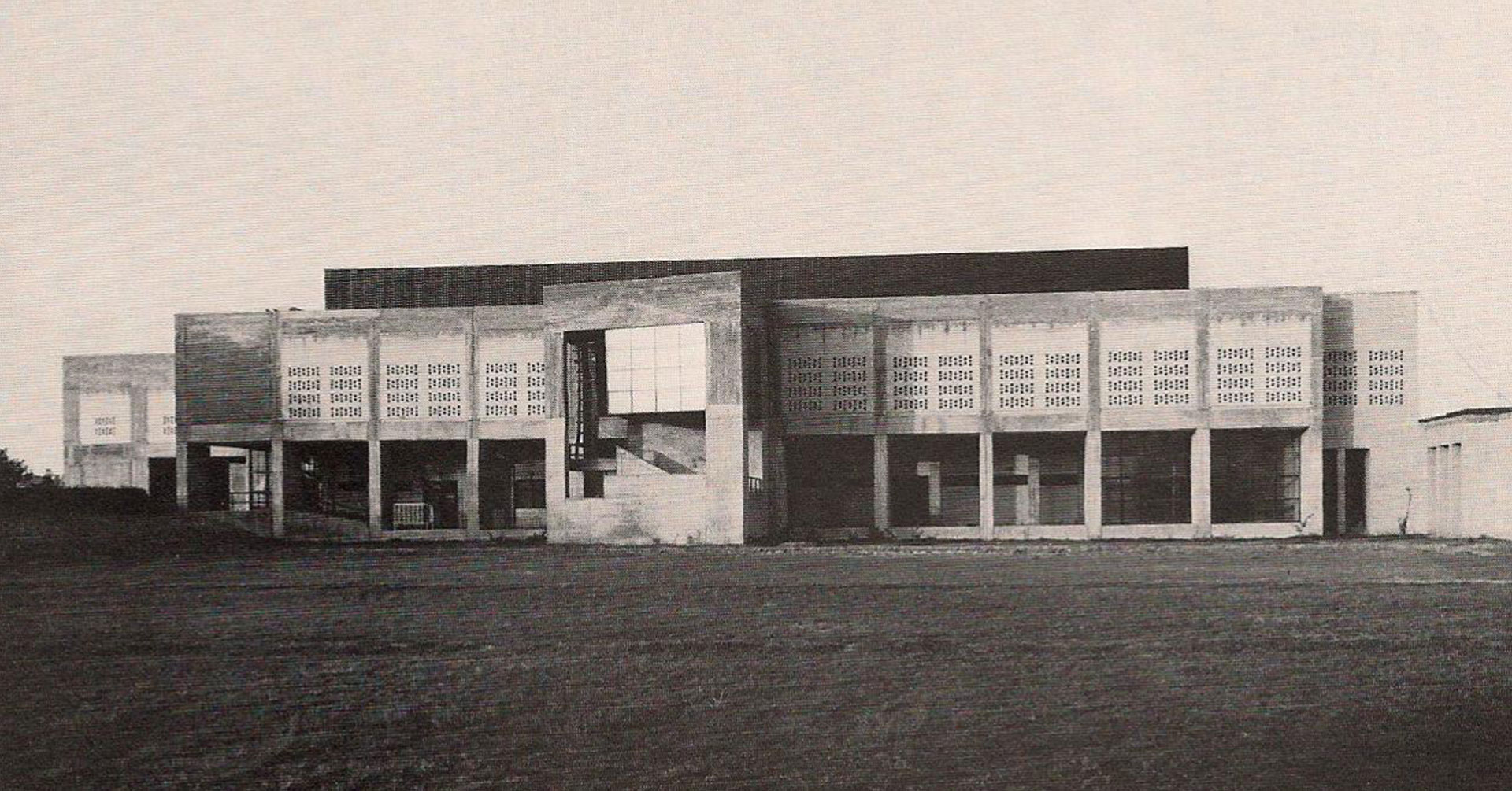

Further along, one arrives at the recently finished gymnasium. In this building an attempt was made to accommodate large shaded areas of arcades and underpasses (south, east and west). This building is located at the end of the walkway, which is meant to continue eastward to the botanical garden and Karoun River. From this east-west pedestrian walk there are three southbound walkways which take the students to the academic section of the master plan, south of the sports fields.

Before building the large gymnasium, we made indoor sports halls and locker rooms, as indicated, to the north of the gymnasium. This building is contemporary to the mosque and student union. At a later date, when we were given the commission for the large stadium, we decided to place it at the south end of the east-west walkway. However, the chancellor of the university forced us to locate it at the north end, which meant painful destruction of the main entrance facade of the sports hall and its integration into the larger structure.

Ironically, this experience taught me a lesson which I utilized in later schemes, namely, that buildings could lack a permanent exterior facade, which inhibits peripheral growth of the structure.

The mystery of many examples of Islamic urban architecture is that facades are internal and are not destroyed or affected by attached buildings. Later, at the request of the university, we made a preliminary proposal for the expansion of facilities. The programme called for a graduate center tor religious studies, where, we successfully argued, some facilities should be jointly used by the student union. This occasion was used to put into practice further expansion and architectural articulation of our open-ended walk-way. Thereby, the exterior facades and external character of buildings are transformed, disappear and give way to a new environment, while the internal facade remains orderly and intact. This was a new discovery for me. I tried to formulate it in a methodology of Islamic vernacular approach to design, which was adopted in the design of some future schemes, such as Isfahan Government and Civic Center and Shushtar New Town.

The university has always shunned the idea of student dormitories, but we took the initiative to preserve land north and south of the student union/mosque axis for future dormitories and final maturity of our east-west axis.

Designing many small schemes which lacked multiplicity and diversity of human activity in the early stages of my career often frustrated me. Consequently, the principle used in most of my schemes was ‘human interaction-intensification program’. This means enhancing the quality and quantity of human interaction by means of physi-cal, spatial organization. The idea of open-ended pathways and maximization of activity along the pathway stems from such an attitude.

In taking Government commissions, we were sometimes obliged to deal with unreasonable technocrats who tried to impose their personal taste on public projects. We always accommodated such whims, keeping our original plans in the drawer, while waiting for the particular technocrat’s term of office to expire. But sometimes we simply showed them what they wanted and built our own design.

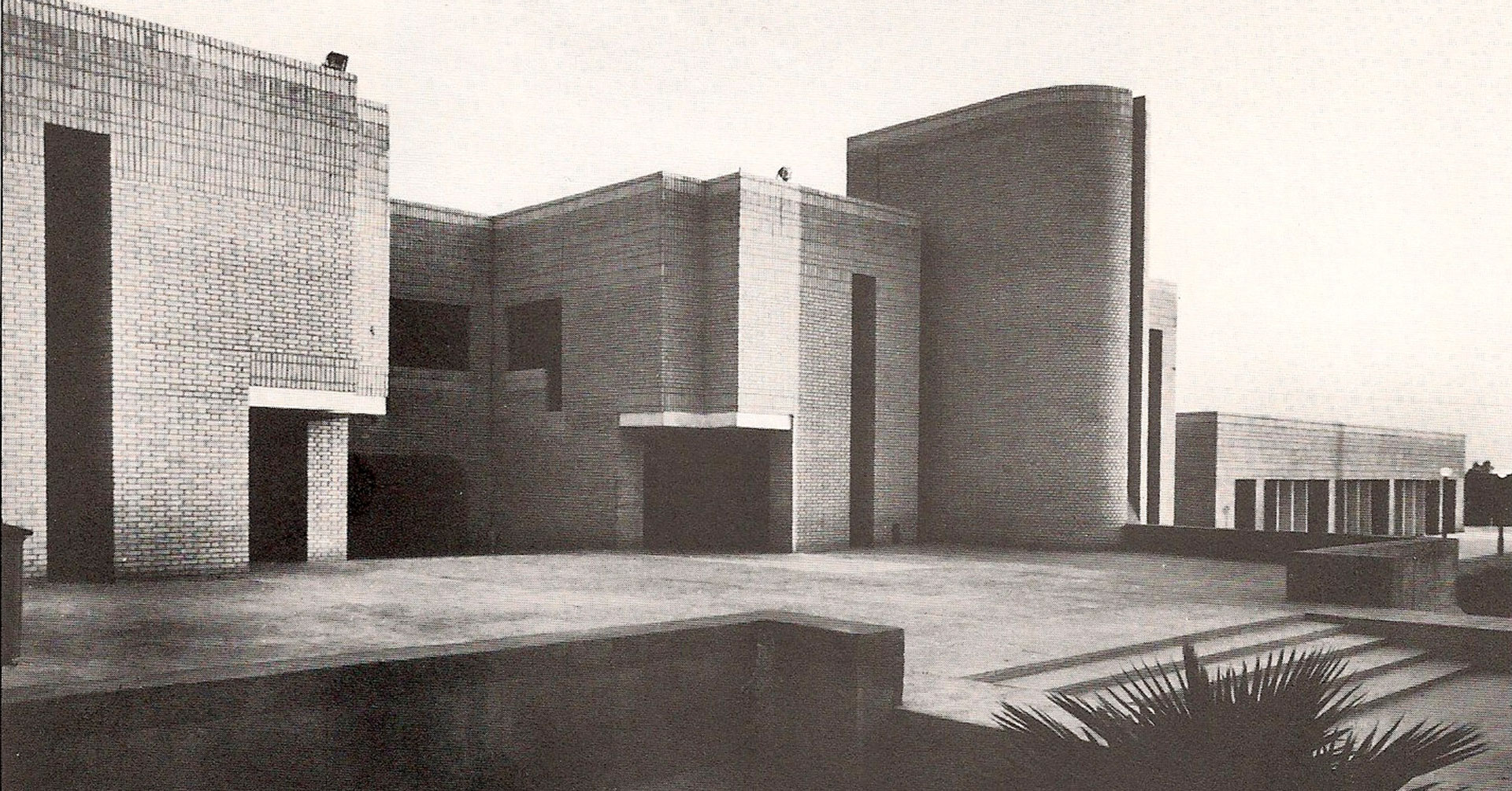

- Administration Building of Jondi-shapour University

- Mosque of Jondi-shapour University

- Student Union of Jondi-shapour University

- Gymnasium of Jondi-shapour University